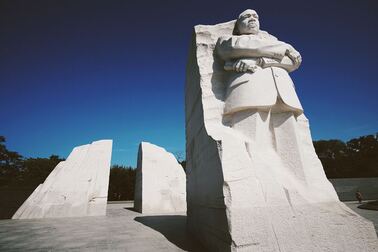

Photo by Brian Kraus on Unsplash Photo by Brian Kraus on Unsplash We’re 12 days away from Christmas, which means I’m eight days away from my winter break. That also means that we’re eight days away from my seniors being done with all of their college applications (pretty much). And the end of applications means, for me, many drafts of the dreaded Loyola Marymount University supplemental essay. This is my sixth senior season, and even though I’ve helped kids apply to almost 100 different colleges, I’ve yet to find an essay prompt that confuses kids more than LMU’s. It looks like something they know, an AP English in-class essay or an SAT writing prompt. It starts with a quotation from Pope Francis, Martin Luther King, Jr., or Father Pedro Arrupe. And then it asks students to answer a specific prompt and “display [their] critical and creative thinking.” So far, pretty standard essay stuff. The challenge comes from the fact that this is not an essay for AP English or the SAT. It’s a college application essay, and therefore, needs to help the reader understand the student better as a unique individual. So now, students need to respond to a fairly abstract prompt, display critical thinking, and share new information about themselves. Not so simple. I was discussing this prompt with one of my students and his mom earlier this week, and she was blown away by the complexity of this question. The student decided to work on the second prompt, responding to a quotation from MLK: “The function of education is to teach one to think intensively and to think critically. Intelligence plus character—that is the goal of true education.’’ The student’s mom sent me an email the next day telling me that she had discussed this topic with some of her colleagues, and they were all amazed at the kind of essay questions kids had to respond to today. Her fascination with this prompt led her to look up the source of this particular quotation, a 1947 piece King wrote for the Morehouse College literary journal, Maroon Tiger, titled “The Purpose of Education.” I highly recommend that you read the full text here, but I want to bring attention to King’s argument, that education is not solely about intelligence. You do not study simply to become smarter. You do not learn simply to gain more knowledge. Instead, King argues, “education has a two-fold function to perform in the life of man and in society: the one is utility and the other is culture.” The first, utility, is something I think most of us agree on. It is to learn how “to sift and weigh evidence, to discern the true from the false, the real from the unreal, and the facts from the fiction.” But the second, culture, is trickier, and so maybe even more important: “Education which stops with efficiency may prove the greatest menace to society. The most dangerous criminal may be the man gifted with reason, but with no morals.” King is speaking specifically of men like Eugene Talmadge, former governor of Georgia and an avid white supremacist. Talmadge was a graduate of the University of Georgia and its law school and a member of the prestigious Phi Kappa Literary Society. But even with this pedigree, King points out that Talmadge still “contends that I am an inferior being. Are those the types of men we call educated?” Clearly, utilitarian instruction is not enough. That instruction must be entwined with the development of character in order to result in a true education. And that leads King to his thesis: “The function of education is to teach one to think intensively and to think critically. Intelligence plus character—that is the goal of true education.’’ King’s formula seems straightforward when separated from the rest of his essay. But in the context of “The Purpose of Education,” this idea becomes revolutionary. And this distinction between knowledge and education is worth thinking about, whether or not you’re applying to LMU. Sometimes the most challenging questions are the ones most worth asking.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

What is the When I Was 17 Project?When I Was 17 is a blog series dedicated to collecting the varied stories of people's career paths, what they envisioned themselves doing when they were teenagers and how that evolved over the course of their lives. I started this project with the goal of illustrating that it's okay not to know exactly what you want to do when you're 17; many successful people didn't, and these are a few of their stories.

Archives

October 2020

|