|

I’m personally of the opinion that no one should start their New Year’s resolutions until February. The first week of January is basically still Christmas. I’m on vacation for a few more days, there are still leftovers in the fridge and treats on the counter, and I barely know my schedule from one day to the next. It’s not the ideal time to introduce major (or minor) life overhauls. So I’m putting off my self-reinvention for a few more weeks.

But even if I’m not ready to start new, healthy habits, it’s always a good time to bail on things that are making our lives harder. So, in that spirit, I want to share three ideas about college and career that I’m no longer buying into, and I hope you’ll join me. A humanities major is not practical. I’ve tackled this one a number of times, and I will undoubtedly keep coming back to this topic, at least until the number of philosophy majors starts going back up again. But the idea that an entire swath of our intellectual arc is useless seems obviously untrue. What is true is that the line from a humanities major to a specific career is less direct, less obvious. But that also means that you can take that major in many different directions, combining your critical thinking and communication skills with your interest in politics or food or entertainment, whatever you really care about. The college you go to will determine how successful you are in the future. It is a truth universally acknowledged by college admissions professionals that it does not matter where you go to college, but rather what you do when you get there. This is so broadly accepted by people in my field that I feel cliché even typing that statement out. But I have to remind myself that this is new information for a lot of students and families. And this is not just my opinion; this argument is supported by numerous studies and experts in the field. For more information, I’d encourage you to check out the white paper from Challenge Success, A “Fit” Over Rankings. It’s too late to [fill in the blank]. In the almost three years that I’ve been working on this series, it has become increasingly clear to me that it is never too late – for anything. You can always change your major, transfer to a different college, get an advanced degree, get another advanced degree, learn a new skill, and take a left (or right! Or U!) turn. That doesn’t mean you don’t have to put thought into your choices or do research to find the right fit for you or plan ahead. You do. But if you find yourself in the wrong program or the wrong city or the wrong job, you can change course and find something that works better for you.

0 Comments

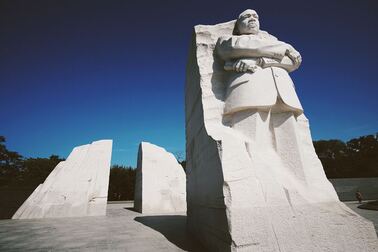

Photo by Matthew Payne on Unsplash Photo by Matthew Payne on Unsplash My goal for all of my seniors is to be completely done with their college applications by the time they go on vacation for winter break. Having that endpoint in mind makes it possible for us to plan ahead and stagger deadlines to hit that mark. Of course, that doesn’t always happen. Sometimes, the end-of-December confluence of college applications and family responsibilities and finals works against that goal, and we find ourselves wrapping things up in January. But for the most part, that deadline is manageable and a really helpful thing to have in mind. In order to get to take that break though, we have to work really hard up until that point. That often means doing things well in advance of the actual deadline, which can be a difficult thing to trick yourself into doing. But if my students can manage it, they get to spend their winter break eating cookies, watching movies, and enjoying time with their families. I also want to spend my Friday after Christmas eating cookies, watching movies, and spending time with my family, so I’m writing this post a week beforehand. That way, I can virtually be in two places at once: posting this on Friday morning and also curled up on the couch with my new Christmas presents. I hope you’re doing the same today. Happy holidays!  Photo by Max Saeling on Unsplash Photo by Max Saeling on Unsplash Last night, I met with one of my sophomores to discuss her Strong Interest Inventory results. I’ve talked about the Strong here before, and how great a tool it is to help young people think about potential majors and careers without being too prescriptive. To that end, I wanted to share how I recommend using the Strong results, both now and in the future. The first resource I share with my students is ONET Online, a website run by the Department of Labor where you can explore careers based on the Holland Code Themes: artistic, conventional, enterprising, investigative, realistic, and social. The careers for each theme are organized by Job Zone, or the level of training required for each profession. Many of my students look at this list and immediately discount careers with lower job zones – but that’s because they’re thinking of their future career, the big thing they’re going to do for decades and decades. Right now, they’re teenagers with only some high school education, perfect for professions in job zones 1 and 2. For instance, one of my top themes is enterprising, which makes perfect sense considering that I run my own small business. But another job under the enterprising umbrella is barista, my college job. Looking back, being a barista required a significant amount of sales and customer service, explaining complex beverages to Starbucks newbies. It’s also important to clearly communicate your needs and priorities to your coworkers in the middle of the after-school Frappuccino rush. And you could say calling out drinks thoroughly and in the correct order is a form of public speaking (double tall nonfat vanilla latte!). These are all skills I learned as a barista that I still use regularly today. Which is why I encourage my students to think about what kind of career they will be inspired and satisfied by 20 years from now, but also what kind of job you might like to do this summer. When I look back on my professional and extracurricular experiences, there are common threads. That’s not because I always knew exactly where I was heading and planned accordingly. Rather, it’s because I’ve always followed my interests (and I’ve been privileged enough to get to do that). That’s what I appreciate so much about an assessment like the Strong, that there is room to move between being a barista and running your own college counseling business, that both jobs can be a good fit for you at different times of your life. And instead of trying to find that one perfect lifelong career, you can just look for the one that’s right for you now.  Photo by Brian Kraus on Unsplash Photo by Brian Kraus on Unsplash We’re 12 days away from Christmas, which means I’m eight days away from my winter break. That also means that we’re eight days away from my seniors being done with all of their college applications (pretty much). And the end of applications means, for me, many drafts of the dreaded Loyola Marymount University supplemental essay. This is my sixth senior season, and even though I’ve helped kids apply to almost 100 different colleges, I’ve yet to find an essay prompt that confuses kids more than LMU’s. It looks like something they know, an AP English in-class essay or an SAT writing prompt. It starts with a quotation from Pope Francis, Martin Luther King, Jr., or Father Pedro Arrupe. And then it asks students to answer a specific prompt and “display [their] critical and creative thinking.” So far, pretty standard essay stuff. The challenge comes from the fact that this is not an essay for AP English or the SAT. It’s a college application essay, and therefore, needs to help the reader understand the student better as a unique individual. So now, students need to respond to a fairly abstract prompt, display critical thinking, and share new information about themselves. Not so simple. I was discussing this prompt with one of my students and his mom earlier this week, and she was blown away by the complexity of this question. The student decided to work on the second prompt, responding to a quotation from MLK: “The function of education is to teach one to think intensively and to think critically. Intelligence plus character—that is the goal of true education.’’ The student’s mom sent me an email the next day telling me that she had discussed this topic with some of her colleagues, and they were all amazed at the kind of essay questions kids had to respond to today. Her fascination with this prompt led her to look up the source of this particular quotation, a 1947 piece King wrote for the Morehouse College literary journal, Maroon Tiger, titled “The Purpose of Education.” I highly recommend that you read the full text here, but I want to bring attention to King’s argument, that education is not solely about intelligence. You do not study simply to become smarter. You do not learn simply to gain more knowledge. Instead, King argues, “education has a two-fold function to perform in the life of man and in society: the one is utility and the other is culture.” The first, utility, is something I think most of us agree on. It is to learn how “to sift and weigh evidence, to discern the true from the false, the real from the unreal, and the facts from the fiction.” But the second, culture, is trickier, and so maybe even more important: “Education which stops with efficiency may prove the greatest menace to society. The most dangerous criminal may be the man gifted with reason, but with no morals.” King is speaking specifically of men like Eugene Talmadge, former governor of Georgia and an avid white supremacist. Talmadge was a graduate of the University of Georgia and its law school and a member of the prestigious Phi Kappa Literary Society. But even with this pedigree, King points out that Talmadge still “contends that I am an inferior being. Are those the types of men we call educated?” Clearly, utilitarian instruction is not enough. That instruction must be entwined with the development of character in order to result in a true education. And that leads King to his thesis: “The function of education is to teach one to think intensively and to think critically. Intelligence plus character—that is the goal of true education.’’ King’s formula seems straightforward when separated from the rest of his essay. But in the context of “The Purpose of Education,” this idea becomes revolutionary. And this distinction between knowledge and education is worth thinking about, whether or not you’re applying to LMU. Sometimes the most challenging questions are the ones most worth asking.  Photo by Djim Loic on Unsplash Photo by Djim Loic on Unsplash I was walking my dog yesterday, and I ran into one of my neighbors. We stopped to chat (while I tried to rein in my dog’s more “playful” impulses), and I asked her how her Thanksgiving had been. She had hosted almost 20 people in her home and had been responsible for the vast majority of the cooking. But she told me that the whole thing had been so manageable this year. When I asked her what she had done differently, she said, “I started doing things a week and a half beforehand. I set my table a week before Thanksgiving. I went grocery shopping and bought all the boxed and canned stuff a week ahead of time. I made a couple of dishes every day last week and just stuck it in the fridge or the freezer. I barely had anything to do on Thanksgiving!” As I walked away, I realized how much this woman’s Thanksgiving advice resembled my own advice to my students. I’ve written before about the benefits of starting early, but it feels particularly relevant at this time of year when I’m wrapping things up with my seniors and getting things going with my juniors and sophomores. I’m also meeting a lot of new families at various stages of the process, and the thing I keep hearing from students and parents is how they just want to keep their options open. The defining quality I see in many of my students as they go through the application process is uncertainty – but I don’t mean that in a negative way. They are uncertain about whether they want to major in marine biology or computer science, but they’re enthusiastic about both. They’re uncertain about whether they want to get recruited for rowing or if they want it to be more of a hobby in college. They’re uncertain about whether they want the spirit of a huge public school with a football team and a marching band and a quirky mascot or if they want the tight-knit community of a small liberal arts school with 150-year-old campus traditions. Either way, they’re excited, as much for the process as for the results. And the best way to give yourself options is to start early. Starting early means getting to decide when it makes the most sense for you to study for and take your standardized tests. Starting early means getting to explore summer programs and apply for internships and part-time jobs. Starting early means getting to sit down for informational interviews with people who work in careers you’re interested in. Starting early really means giving yourself time to try different things, a necessary step in the process of figuring out what you care about. So whether it’s Thanksgiving dinner or applying to college, do yourself a favor and start a little bit early. |

What is the When I Was 17 Project?When I Was 17 is a blog series dedicated to collecting the varied stories of people's career paths, what they envisioned themselves doing when they were teenagers and how that evolved over the course of their lives. I started this project with the goal of illustrating that it's okay not to know exactly what you want to do when you're 17; many successful people didn't, and these are a few of their stories.

Archives

October 2020

|