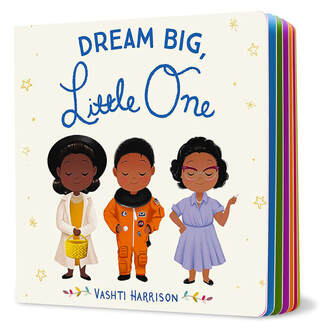

One of the first things I did after hearing about George Floyd’s death and the protests that have since followed was become a subscriber to The Conscious Kid, “an education, research, and policy organization dedicated to equity and promoting positive racial identity development in youth, […] [and] taking action to disrupt racism in young children.” I was inspired to join after seeing their post about “41 Children’s Books to Support Conversations on Race, Racism, and Resistance,” and I’ve been so energized by the articles, webinars, and initiatives they have been sharing every week. As the proud holder of a graduate degree in English, I have always been a little obsessed with books, especially those books I read as a child that set me on the path to studying literature. You can practically draw a straight line from my love for D’Aulaires’ Book of Greek Myths and my eventual decision to major in classics in college. And I’ve always been enthusiastic about sending books to the little kids in my life so they, too, can enjoy the antics of the monkeys in Caps for Sale or giggle while reading Dr. Seuss’s “Too Many Daves.” Combining the pleasure of reading children’s books while fostering a greater awareness of racial inequality seemed like a natural fit. So I immediately hopped on Google, found a couple of Black-owned bookstores, and sent a stack of children’s books to my friends and family. My favorite one is part of a series by Vashti Harrison, called Dream Big, Little One. This simple board book features stylized illustrations of notable Black women like Katherine Johnson, the famed NASA mathematician; science fiction author, Octavia E. Butler; and – no introduction necessary – Oprah. But there were a few women in the book that I had never heard of before. And in the spirit of the When I Was 17 project, I wanted to share their stories here. Mae Jemison was the first Black woman to travel into space aboard the Endeavour. But every time I thought I had a handle on Jemison’s story, she threw another curveball at me. Her biography highlights her early love for science, fitting for a future astronaut, and the discrimination she faced as a woman of color trying to enter that field. But Jemison was also an accomplished dancer, studying African, Japanese, ballet, jazz, and modern dance. She attended Stanford University when she was only 16 and studied chemical engineering. But instead of going the route I expected, Jemison went on to earn her medical degree at Cornell University before serving as a medical officer in the Peace Corps in Liberia and Sierra Leone and later working for the CDC. After her time abroad, Jemison returned to the US and began taking graduate-level engineering courses. She was inspired by the rise in female astronauts like Sally Ride and applied to the NASA astronaut training program. She was accepted to the program in 1987 and completed her 8-day space mission in 1992. She has since founded her own company examining the impacts of technology on society, taught environmental studies at Dartmouth College, and worked to encourage minority students to study STEM. Augusta Savage was an internationally recognized sculptor and teacher who was part of the Harlem Renaissance. Savage started her career at a very young age, making small animal figurines out of the red clay she found near her home in Green Cove Springs, Florida. Her father was not very supportive of this hobby, but by the time she got to high school, Savage was teaching clay modeling classes to the other students. At age 27, she won the prize for most original exhibit at the Palm Beach County Fair and then moved to New York to study sculpture at Cooper Union. She was a dedicated advocate for equality, inspired partly when a French art program denied her application because she was Black. She did eventually travel to France in 1929, where she won awards at Paris Salons and Exhibitions. Back in the US, she founded the Harlem Community Art Center where she taught classes to anyone who wanted to learn about art and sculpture. Savage was also selected as one of only four women and only two Black artists to create works for the 1939 New York World’s Fair. Her piece, Lift Every Voice (“The Harp”), was wildly popular. She later moved to the Hudson Valley and spent the rest of her life teaching art, writing children’s books, and running two successful galleries. One of her busts, Gamin, is on permanent display at the Smithsonian American Art Museum.

1 Comment

Photo from Canva Photo from Canva Today is Juneteenth, a holiday commemorating June 19, 1865, the day the last enslaved persons were officially liberated in Texas. This happened two and a half years after Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation, and almost six months after the Senate passed the 13th Amendment which declared, “Neither slavery nor involuntary servitude, except as a punishment for crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted, shall exist within the United States, or any place subject to their jurisdiction.” I’m not sure I’d ever read the text of the 13th Amendment before. It’s not the full-throated denunciation of slavery that I thought it was – you can see a straight line from the gaping loophole this amendment allows and the current problem we have with mass incarceration. In reading about Juneteenth this year, I was repeatedly struck by the fact that I don’t remember learning about this holiday when I was in school. Maybe it was in one of the side boxes in my textbook that seems designed for busy students to skip over as they race through their assigned reading. In talking to my mom, she also didn’t recall hearing about Juneteenth when she was in school. But I was caught off guard that my younger sister also did not remember learning about it – and her entire education took place in the 21st century. In a blog post on Education Week, Washington and Lee student, Briyana Mondesir explains, “A lot of the way that schools depict [B]lack history, our history, is: [w]e were slaves, then Martin Luther King happened, and then everything's fine.” That sounds like an oversimplification, but that’s not far off from my memory of learning about Black history in high school. History teacher, India Meissel goes even further: “It's not just that teachers don't discuss the day, and its significance, in class. Many don't know about Juneteenth themselves. Meissel “remembers leading summer history and social studies trainings for elementary school teachers who had never heard of the day.” So if Juneteenth was not a notable part of your education, as it wasn’t for me, we now have the opportunity to go back to school and try again. We get to dig into the reality that “emancipation wasn't a single point in time—it was a process,” as Meissel explains. Juneteenth is a cause for celebration, an independence day that included all Americans for the first time. And Juneteenth is a beginning, not an end. It’s heartening to see the attention this holiday is getting this year. At Collegewise, we are officially taking the day off from work, and as my colleague Arun said, “As you see fit, make it a wonderful and meaningful day!” In that spirit, here are some of the things I’ll be reading, watching, and listening to today:  Photo by Thought Catalog on Unsplash Photo by Thought Catalog on Unsplash The conversations I’ve been having this week in my home, in my friend groups, and in my professional circles have naturally focused on the protests happening across the country and the renewed call for equity in our society, especially equity for Black people. I have been so appreciative of the vast amount of resources, from films and interviews to books and articles, that people have been sharing on social media. One blog post in particular has stuck with me all week, shared by another independent education consultant in the Facebook group for ACCEPT (I talked about ACCEPT and the work they’re doing last week). The author, Sydney Montgomery, talks specifically about how IECs can use their roles to advocate for a better, anti-racist system of college admissions. In particular, Montgomery points out the insufficiency of doing pro-bono work with low-income students of color, writing, “I want to challenge this conflation of Black students with pro-bono and poor students. Black students aren't just found in CBOs, non-profits, Boys and Girls Clubs, and low-income neighborhoods. The repeated fusing of "low-income" and "minority" perpetuates the stereotypes that most Black students are poor and disadvantaged. It sets up a dichotomy that most students are either rich and White or poor and Black. This is a dangerous mental schema for those of us in this profession. Too often the only time Black students are mentioned by consultants is in reference to their income or state of being underprivileged.” She goes on to ask, “If you are genuine about anti-racist work and committed to dismantling White supremacy, the question I want to ask you is whether you feel just as passionate about helping dismantle systemic racism for the wealthy Black student with straight As as you do the archetypical "low-income" Black student from a poor neighborhood. I'm not saying that these students have equal advantages or are the same, far from it, but what I am saying is that fighting systemic racism cannot just be confined to pro-bono work. Studies show that Black and minority students undermatch in the college application process across all socioeconomic statuses.” That last point was eye-opening to me, but it shouldn’t have been. Of course Black and minority students face greater barriers to access in higher education regardless of their backgrounds. And this problem does not go away once students get admitted to highly selective universities. Just think of stories like the Smith College employee who called the police on a Black student eating lunch on campus, or the White Yale student who called the police because a Black graduate student was taking a nap in her dorm common area. It is merely luck that those situations did not end in tragedy like so many other interactions between the police and Black people. In addition to her own perspective on the challenges facing Black students in higher education, Montgomery takes the time to share some valuable resources, like Dr. Beverly Tatum’s seminal work, Why Are All the Black Kids Sitting Together in the Cafeteria?, and organizations working to make an impact in this area like the National Society of Black Engineers and the National Black Law Students Association. I would highly encourage you to read the full post and check out the resources Montgomery suggests.  Illustration credit: SacréeFrangine Illustration credit: SacréeFrangine Two months ago, it felt strange to talk about college admissions topics without acknowledging the big, virus-shaped elephant in the room and how it was impacting everything from standardized test policies to waitlist trends. That feels even truer this week in the wake of George Floyd’s murder and the subsequent international protests that have been taking place. With that in mind, I want to use this space this week to highlight some organizations that are working to create greater access and equity in higher education, an important piece in dismantling the racist systems that lead to deaths like George Floyd’s, Breonna Taylor’s, Ahmaud Arbery’s, and many others. As the Minneapolis-based organization MPD150 writes: “To really ‘fight crime,’ we don’t need more cops; we need more jobs, more educational opportunities, more arts programs, more community centers, more mental health resources, and more of a say in how our own communities function.” ACCEPT: Admissions Community Cultivating Equity & Peace Today ACCEPT’s mission is to “empowe[r] college admissions professionals who seek to center anti-racism, equity and justice in our work and communities.” They want to “lead the college admissions profession in creating an equitable, just, and anti-racist path to post-secondary education” by centering “the voices of communities marginalized in secondary and post-secondary education” and “as educational ‘gatekeepers,’ remov[e] barriers to post-secondary education.” ACCEPT advocates on behalf of students through the Direct Support Initiative, reaching out to colleges and universities whose problematic policies have harmed students, particularly BIPOC students, to hold these schools accountable. They have also been instrumental in pushing universities to adopt more equitable practices in the face of the disruption caused by coronavirus, namely extended decision deadlines for high school seniors and test-optional policies for Class of 2021 applicants. You can learn more and get involved here. The National Center for Fair and Open Testing (FairTest) Founded in 1985, FairTest has spent the last 35 years “promoting fair, open, valid and educationally beneficial evaluations of students, teachers and schools [and] work[ing] to end the misuses and flaws of testing practices that impede those goals.” My experience with FairTest has primarily been through their advocacy for test-optional admissions policies at four-year universities. It is broadly acknowledged that the SAT and ACT are substantially biased against Black and Brown students and has been since its inception. As the Harvard Civil Rights-Civil Liberties Law Review notes, “Carl Brigham, the inventor of the original SAT, was a eugenicist and wrote that the test would help prove the superiority of the white race.” Even Brigham eventually “acknowledge[ed] that scores had little to do with natural intelligence and more to do with ‘a composite including schooling, family background, familiarity with English and everything else, relevant and irrelevant.’” This continues to be a problem almost 100 years later and presents a clear barrier to higher education for many BIPOC students. |

What is the When I Was 17 Project?When I Was 17 is a blog series dedicated to collecting the varied stories of people's career paths, what they envisioned themselves doing when they were teenagers and how that evolved over the course of their lives. I started this project with the goal of illustrating that it's okay not to know exactly what you want to do when you're 17; many successful people didn't, and these are a few of their stories.

Archives

October 2020

|