One of the joys of growing up is seeing your friends become the schoolteachers who had seemed so grown-up and mysterious when we were kids. And the best part about that is getting to see how much energy they put into their work and how much delight they get out of it. Jennie Drummond is a high school art and yearbook teacher and a wonderful example of exactly that. Our conversation has been edited for length and clarity. When you were 17, what did you want to be? I had no idea. When I was growing up, I wanted to be a dinosaur – a stegosaurus. I even painted one on my fanny pack. Then, when I found out I couldn’t be a dinosaur, I wanted to be a paleontologist because that was the closest I could get. So that’s what I was going to be until I was 15. But then I realized the necessary amount of math and science I would have to do to become a paleontologist, and my math background was not very strong. So I decided, “You know what, I like to draw. I'm going to be an artist and live in a box.” In my senior year of high school, I was in a class that was really important to me, comparative government and comparative literature. The second to last week of the school year, we were given an assignment to answer the prompt, “How are you going to save the world in five years?” And I didn’t know how me being an artist was going to save the world. I had also been an activist in high school. I was the president of the Gay Straight Alliance, and this was during Proposition 8 too. I was inspired by my own coming out; I recognized that just because my family loved and accepted me immediately doesn't mean that everyone else's family does. But I hadn't really come into my own or become confident in it yet. I just thought that that would end in high school too. So I was trying to figure out what to do to save the world in five years. We were all sitting outside, and my teacher, who is described as the living embodiment of Atticus Finch, sat down next to me and asked, "So, what are you gonna do?" I told him I had no idea, and I started crying because I was taking this so seriously. And he just said, "That's funny, because I always thought you'd be a teacher," and got up and walked away. And I just thought, “Oh.” So I ended up delving into that and realizing that, yes, when I was growing up, I had been teaching my dinosaurs how to spell. I started recognizing that that had always been there, but I had never noticed it as a possibility. So I decided that I was going to save the world in five years by becoming an art teacher in my hometown. How did you decide to attend Chapman University? I went straight into college, but I wish I hadn't. Chapman wasn't really a good fit for me. I went there because my best friend was going and they had a decent art program and a political science program, and I wanted to study both of those. But it was a bit of a superficial environment, part of that Orange County culture. And while I was there, Chapman decided to become more business focused and they funneled a lot of the funding away from the humanities and into the business school. I am glad that I went to a small school, and I did meet one of my best friends, and if I hadn't gone to Chapman, I wouldn't be in the job that I'm in right now, but overall, it wasn’t a good fit for me. How did you choose your major? I went in as an art and political science major, and that’s what I graduated with. I also started my teaching credential in social sciences and fine art while I was there, which is how I was able to start teaching at 21. How did you get from college to where you are now? I graduated a semester early because I wanted to come home. I moved back home for a few months and started working as a substitute teacher. I had gotten hired on when I was home for Thanksgiving break so I could start working right away in January. I also got a job as a helper at a dog groomer, so I got paid to play with dogs. I love dogs and that ended up being my second job for three years. After that semester, I became a long-term sub and then a history teacher at San Ramon Valley High. Then I got hired as an art teacher at Monte Vista the following year. Originally, I loved teaching both history and art, but now that I've been teaching art, I wouldn’t want to go back to teaching social science. I love social studies, but when I was teaching history, it was me lecturing or me facilitating something. Whereas with art, I'm able to have a lot more of a personal relationship with my students, I can talk to every student every day, and in social studies that's not an option. I thought I got into teaching because I wanted the students to be smarter, but I think the real reason is that I want to help them be better humans and be kind and this is the easiest way to model that. The fun part of teaching is that I get to play with all these different mediums all the time, so I don't feel pigeonholed into one. My favorite is watercolor because 70 percent of the time, watercolor does what you want, and the other 30, it's like, "Hee-hee, you've gotta figure it out!" I also love ceramics, and I've been doing a lot more acrylic painting recently. In the past year, I've been showing my art outside of school. Part of it is because I need the second income, but it's also fun. I just got into my first juried show and I was the youngest one who was accepted by at least a decade. The opening was a couple of weekends ago, and it was so validating to have other people care about what I’m making. It’s also meaningful in trying to show my students that there is room for creativity as an adult, whether it be as an artist or an engineer or whatever they want to be. I also started to teach yearbook a few years ago. When I was in college, I started taking graphic design courses, and I fell in love with book design and typography. I'm fortunate to have a group of kids that are really passionate about it. One of kids described it as how every family has the weird cousin, and yearbook is like putting all the weird cousins in the same room together. It's a really fun environment, and it's so gratifying to see their faces when they open up the boxes and see this book that they made. I also just got admitted to a master’s program. I never really considered getting a master’s before. I didn't want to get a Master of Education because it’s basically just five more classes after your credential. And I didn't want to get a Master of Fine Art because I didn't want to spend time working on an MFA if I didn't want to make a career out of being an artist. Then this program at the Art of Education University showed up offering an MA in arts education. What I'm doing in this program immediately applies to the classroom. And then I’m also improving my artistic craft, taking studio classes. My next class is a photography class and I'm stoked. And in a way, it’s also validating that this is what I want to do, this is my career. That feels really good. My main goal is to always get better. I think that my teaching is evolving in advocating for more funding for the arts and for my program. And in continuing to find ways to empower my students. I think that's one thing that I will always be able to improve is getting my students to advocate for themselves, to view themselves as artists and creative people, as people who have improved and grown throughout the year, and as people who have value and can create something worth creating. I think that is going to continue to be my main focus. Looking back, what seems clear to you now? I wish I had known that not everybody loves college. I felt like I was doing it wrong, instead of recognizing that if the best years of my life are from 18 to 21, then I’m probably doing that wrong. It just continues to get better. The other biggest thing I wish I’d known is that everything ends up okay. I think that at 17, coming into my own as queer person, I felt like I was wrong, broken, hollowed out. Looking back now with a supportive partner, with supportive friends, and an incredible family, I can see that you do end up okay. I would tell people to make time for yourself. That therapy is always a good thing. And that it's okay to switch it up. I think its been very helpful for me to see people like my dad, who stayed in the same line of work his whole life, or like my mom and my mentor who switched their entire careers partway through.

0 Comments

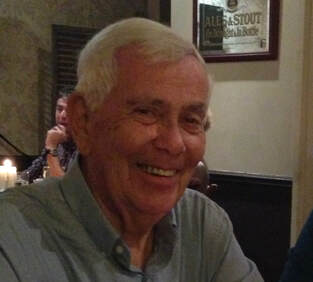

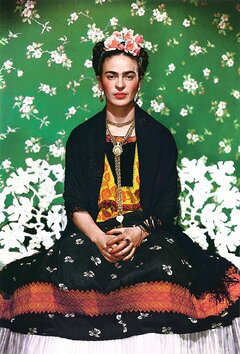

Howard Henderson is a former educator and entrepreneur, a teacher and principal who went on to start two successful companies. He is also the first person I’ve interviewed who is retired and at the end of his career path. In looking back over his 50+ year career, the same lessons emerge that we’ve been talking about throughout this series: stay flexible and open to new opportunities, carve out your own space that fits with your strengths and interests, and don’t worry about knowing the end point right from the beginning. Our conversation has been edited for length and clarity. When you were 17, what did you want to be? I grew up in a small town about 40 miles east of Cincinnati, a town of about maybe 1,200 people. It was a perfect place. That was in the 40s and 50s. It was a great place for kids to grow up in. You could ride your bike anywhere you wanted to. Everybody in town knew you. It was very comfortable. We went swimming in the creek. We played tag. I worked at the Kroger grocery store. It was pretty much a traditional Midwestern town in the 1940s and 50s with parades and all those kinds of things. I had a high school basketball coach who was also an American history teacher. He had come to the school when I was a freshman in high school. He was young and easy to talk to. Our first year, our record was 3 and 13 - terrible. We didn't know which end to shoot at. But we came along. By the time we graduated, we were much more successful, and it was fun. So I thought I wanted to do that. I really like American history, I really like sports, so I thought I’d be a teacher. My dad was not particularly excited about me being an educator. He had his own business, a savings and loan bank that he had inherited from his father. It had been in the family for a couple generations. I tried to be fair and say maybe I could do that, but I had no interest in it really. I'm sure my parents were a little disappointed, but it all worked out. How did you decide to attend Ohio University? There was no doubt that I was going to go to college. My parents were both college grads, so I never thought about it much. My parents told me I was going to go to Ohio University, so I never looked at any place else. My uncle had a PhD and had been involved with the government in DC. His son, who was the same age as me, had gone to private schools on the East Coast, so they had eastern influence. My uncle knew the president of Ohio University and said that I should go there. That's the crazy, true story. How did you choose your major? I went in as an education major. It was comprehensive social studies, so I got a lot of history, geography, and economics. Because of my dad's wishes for me, I decided maybe I should go into business administration. In my sophomore year, I took some business administration courses, and I hated it. My dad was very happy that I was going to try it, but I tried it and I hated it. So I switched back to education. How did you get from college to where you are now? I graduated with my teaching credentials, but I went into the Army as soon as I got out of college. I graduated young, I was always the youngest one in my class, and I just decided that I wasn't ready to settle down. Kids take gap years nowadays. Well, gap years weren't around then, so I signed up for the voluntary. I was in for about 18 months. There was no war going on at that time - I was very fortunate. I was mostly at Fort Hood, Texas, Camp Carson, Colorado, and Camp Polk, Louisiana. We were learning how to drive the tanks, the gunners, and all those kinds of things, playing soldier. When I was in Fort Hood, I was in a truck wreck and I screwed up my knee. After that, I was assigned to a nurse, Major Lad. She was the head of the pharmaceutical places at Fort Hood. She was really tough; she knew more bad words than I could even think of, and she kept me in line. The reason I got the job working for her was because I could type. Not very well, but it was good enough for Major Lad. I spent almost a year with her. It was an easy job. I didn't have to wear khakis. I didn't have to show up for morning drill, or anything. I just went to her office and worked in the pharmacy. It wasn't bad at all. Then I came out and started teaching. I went back to Ohio, to Hamilton which is just north of Cincinnati. I took a job coaching and also teaching what they called adjustment classes, or special education now. That's what I was hired to do, but I didn’t have a clue. They didn't even have certification for it yet. I said, "I don't have any training," and they sent me to a two-day workshop in Columbus. I went and I was the youngest person in the room by probably 40 years. I got some training then, but I had no skills. I was worn out every day. We did okay, but I don't think anybody had a clue what to do with special kids. I was there three years, and then I went to another school in Hamilton. I was coaching and I taught physical education for two more years. By this time, I was starting to get the message that I needed to get my master's. I started on my master's at Miami University in Ohio, which was an excellent school. After I got my master's at Miami, I went to Bowling Green and picked up a specialist degree, which was two more years. Then, I was going to get my doctorate, but at that point, you had to give up your present job and income, and be a graduate assistant. I couldn't afford to do that because I had two kids. But I did get a two-year National Science Foundation grant to go to Stanford where I met great people. After I got my degree, I started applying for principalships. I was not impressed with what I was doing as a teacher, and I thought I could do a better job as a principal. I became an assistant high school principal, then a junior high school principal over a five or six year period. After I'd been a principal, I applied for supervisory jobs and I moved up to a director of instruction position, then a supervisor, then an assistant superintendent of schools. When I got to assistant superintendent for curriculum instruction, I stayed in that job for 18 years. I was in a district that had about 700 teachers, which was a pretty good-sized district. This was the Lyndon Johnson era, and Johnson got a lot of money for schools. It was called the Elementary and Secondary Education Act. Some of it was for teachers' salaries, and a lot of it was used to get updated audio-visual equipment: slide projectors, tape recorders, the kind of stuff we laugh at now. I stayed in that role for 18 years because it was great. I got a number of National Science Foundation grants to go places to learn about what was going on. I went to Stanford, University of New Hampshire, Michigan State, and met some of the leaders in the field. Then I used some of the money in our district to get those leaders to come to Mansfield, Ohio to work with our teachers. We got a lot of recognition from that, and we were written up in a lot of journals. We were working on how we could reorganize classrooms, so they worked better for kids; making things interdisciplinary, putting different courses together that complement one another like social studies and literature, or science and math. Our staff was so excited. These consultants would work with us all day, and then they would hang out. It was really relaxed atmosphere. To be involved and see teachers get better was a real thrill. I retired from that position in 1985, and then I started my own company. There were small, mostly Catholic schools throughout the Midwest that were going bankrupt because they had no money. The reason they had no money is that they had no graduate programs. Graduate programs make money. A friend of mine and I, we decided that we could help those schools. We would go in and write their curriculum, and get it approved by their state Department of Education and the North Central Association of Secondary Schools and Colleges. Then we would hire people to teach the courses. We brought graduate education to where the people were, rather than having to take the graduate students to the home campus. For example, in Wisconsin, the University of Wisconsin's a great school, but you have to go to Madison. There are people throughout the rest of the state that didn't have higher ed at that time. So we set up programs all over the state, and then did the same thing in Minnesota, Iowa, Illinois, Michigan, Ohio, and Indiana. We did that from '85 until I bought out my partner in '94 and then I sold the company in 2003. I also started a company with a woman I knew from Ohio State. She and I wrote a learning style inventory that students could take, and we could identify their learning strengths. The teachers could then adjust their teaching to the strengths of the student, and they could learn more. Simple concept, but hard to do. There had been a few done before, but there had never been any that were normed. I was doing the practical part and she was doing the database stuff, tabulating numbers and looking for trends. We did a lot of work with schools that had foreign students who came to the US for higher ed. And we did a lot with industry too, like General Motors and Bell and Howell. I bought my partner out in 2000, and I kept that company and ran it until 2013. I was done traveling, flying someplace every week. So I sold it and retired. I miss my jobs. I had to retire, but I miss it, the connection with people, the enthusiasm. I've never been one to say, "I can't wait to retire." Looking back, what seems clear to you now? Professionally, I think I was blessed. I was at the right place at the right time. I got breaks that I don't know how I got, and I was really excited about it. I wouldn't change anything in my professional career. I really wouldn't. Eventually, I got tired of traveling, but I felt so full. I had something to help people with. One of the advantages I had was that I was the first person to hold that particular position in most of the places I worked. So I got to organize what I was going to do. They basically said, "Here's what we want to have done," and then I would figure out how to do it. I never had to follow anybody. My advice is to find something you have enough confidence in that you think you can make it work, and then go for it. A few months ago, I shared a post on the Strong Interest Inventory (you can refresh yourself here), introducing the six occupational themes: artistic, conventional, enterprising, investigative, realistic, and social. But identifying the main theme or themes that align with your professional interests is just the start. The next step I like to take with students is to introduce them to O*NET Online. Now, prepare yourself. O*NET Online is affiliated with the US Department of Labor, which means they have an absolute treasure trove of information about prospective careers. But, like many government websites, it’s not the most aesthetically pleasing. I often talk to my students about not ruling out a particular college because their website is hard to navigate – a difficult website does not correlate to a poorly run college. And the same thing applies here; just because O*NET Online isn’t straight out of a Squarespace advertisement doesn’t make it any less useful. The first place I bring students is to the Advanced Search tab, which allows you to look for jobs based on occupational themes or, as they call them, interests. Clicking on “Realistic” will take you to 100 sample professions that fall in that category, organized by “job zone.” This is one of my favorite elements of O*NET Online. Job zones correspond to the level of training required for a particular profession from 1 (little training) to 5 (extensive training). What I love so much about this is that it distills each occupational theme down to its fundamental quality. For example, a realistic occupation with a job zone of 1 would be a fast food cook. It’s a concrete task that involves things rather than concepts and follows a set procedure that gets executed repeatedly. A realistic occupation with a job zone of 5 would be a surgeon. Again, a concrete task that involves things more than concepts and follows a set procedure; but repairing human bodies is more complicated than making hamburgers and thus requires much more training. You can also combine themes in the advanced search, looking for jobs that are both realistic and social (like a sheriff or an athletic trainer). And the advanced search results indicate green occupations that are going to be in greater demand as we move toward a green economy, like bus drivers for example, who will be more and more necessary as larger numbers of people start taking public transportation. There is also a designation for jobs that have a bright outlook, or are likely to grow faster than average, increasing 10% or more over the next 10 years. While O*NET Online might not be the shiniest website you’ve ever seen, it is a wildly helpful place to start getting ideas for prospective jobs that fit your occupational themes. I encourage you all to start playing around with it and to find the the careers that are right for you.  I’ve been in Mexico City for the past month, and yesterday, I finally had the opportunity to visit Casa Azul, Frida Kahlo’s home and now a museum dedicated to her life and her art. Because I am a nerd, I opted to get the audio guide so I could learn as much as possible. In the very first room of the house, we were directed to a portrait of Kahlo’s father, Guillermo. The audio guide pointed out the curious background of the painting, regularly space orbs that resembled cells as seen through a microscope. The guide explained that, as a child, Kahlo had been enamored with science and hoped to become a doctor. I was shocked by this new perspective on a woman who seemed born to be an artist; the idea that she almost went in a completely different direction felt at odds with the aesthetically complete version of Frida I’d come to know. But as I’ve talked about many times, we’re all far more complex and contradictory than we initially present ourselves. And so I’m enjoying the idea of Frida Kahlo, the artist, alongside Frida Kahlo, the doctor. Kahlo’s evolution inspired me to look for other iconic people who almost didn’t end up in the profession with which we so fully identify them. Like John Grisham, who leveraged his 10-year career as a lawyer into his current profession as a celebrated author of legal thrillers. Or Vera Wang, who spent 15 years working as a fashion editor at Vogue before designing her own wedding dress and launching a wildly successful bridal line. Or Harrison Ford, who was working as a carpenter for none other than George Lucas who thought he would be perfect for a role in his new project – Star Wars. My favorite story was about Jonah Peretti, founder of BuzzFeed and co-founder of The Huffington Post (and brother of comedian Chelsea Peretti – what a family). Peretti attended University of California, Santa Cruz where he majored in environmental studies. He then moved to New Orleans and taught computer science at a private high school before going to grad school at MIT. While procrastinating on writing his master’s thesis, he started exploring Nike’s new service for customizing your own sneakers. After submitting a few unsavory words that got rejected, he tried the word “sweatshop,” which launched an email back-and-forth with Nike that he forwarded to a few friends. The email thread eventually reached millions of people and Peretti ended up on The Today Show discussing labor practices with Nike’s head of PR, launching his career in media. Like Jonah Peretti, Frida Kahlo ultimately found her way to her vocation by leaving room for chance. As a child, Kahlo suffered from polio and, while recuperating, she took to drawing pictures in the fog on her window to entertain herself. Years later, when she had to spend months in bed after a horrific bus accident, her parents gave her an easel and a set of paints she could use while lying down all day. There was even a mirror installed directly over her bed so she could see herself and paint the self-portraits she is best known for today. As these stories and many of my interviews illustrate, we can only plan so much before something upends our intentions. Sometimes those disruptions are fortunate, like Peretti’s email thread, and sometimes they’re devastating, like Kahlo’s accident. But, fortunately, there’s no expiration date on choosing a different path. We can always learn something new, try something new, or reinvent ourselves. And in the end, we might find a version of ourselves that fits even better. |

What is the When I Was 17 Project?When I Was 17 is a blog series dedicated to collecting the varied stories of people's career paths, what they envisioned themselves doing when they were teenagers and how that evolved over the course of their lives. I started this project with the goal of illustrating that it's okay not to know exactly what you want to do when you're 17; many successful people didn't, and these are a few of their stories.

Archives

October 2020

|